About The Wellington Basin

It was no small task turning this swampy piece of land into a ground suitable for cricket and recreation.Here, we look at its transformation from lagoon to land.

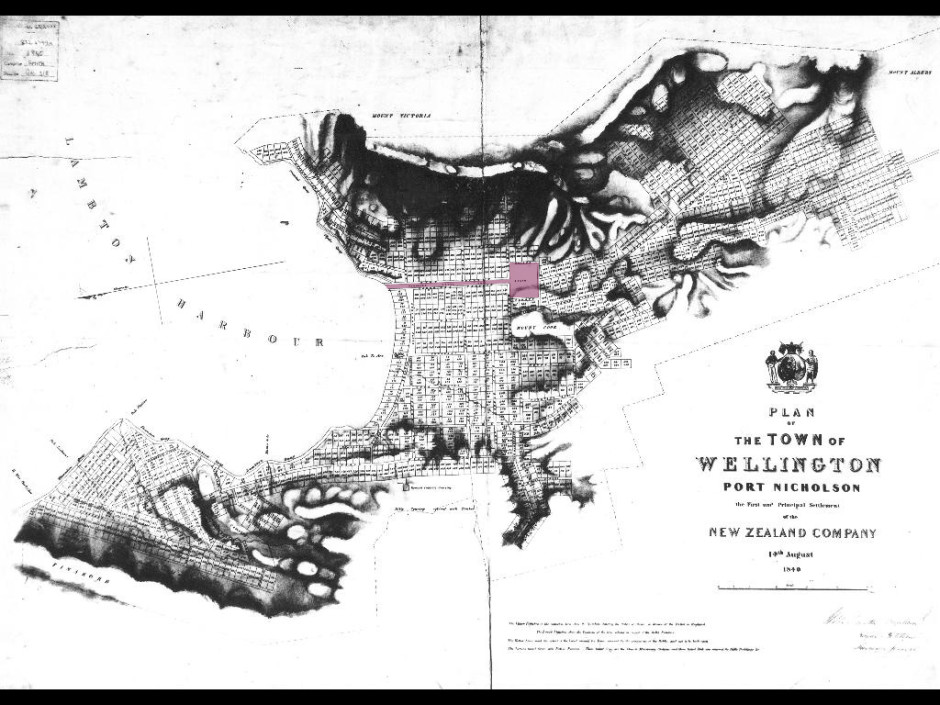

When Surveyor-General, Captain William Mein Smith, drew up plans for Wellington in 1840, a stream linked the harbour to a lagoon that he simply labelled ‘Basin’. Smith’s intention was for this Basin to become a safe harbour for ships, accessed through a canal to the harbour. Over the next fifteen years the city continued to develop around Smith’s Basin as people from around the world moved to the new colony.

Then an earthquake changed everything. At 9.11pm on January 23 1855 an earthquake struck. Estimated at a magnitude of 8.2, the quake was centred in the Wairarapa but had a profound effect on Wellington’s landscape. Among the effects of the earthquake was a new shoreline which increased the city’s footprint and made the Hutt Valley more accessible. It also saw the land through Te Aro rise by about 1.5 metres, turning Smith’s Basin into a swamp.

In 1857 citizens began to petition the Provincial Council for a site to create a permanent cricket ground. With the city growing rapidly, cricket fields were being built upon as quickly as they were developed and the English settlers passion for the game would not abate. The Council approved the petition and gave them the site they desired, Smith’s former Basin at Te Aro.

It was no small task turning this swampy piece of land into a ground suitable for cricket and recreation. However, the prison at the nearby Mt Cook barracks offered free labour and, in February 1863, prisoners began the task of draining and flattening the new ‘Basin Reserve’. While the work to reclaim land from the earthquake-inspired swamp was successful, the Basin Reserve’s place as the home of cricket was not confirmed until it was leased for cricket in 1866. Cricket’s love affair with the Basin Reserve had begun.

The Basin Reserve’s long association with cricket began on January 11 1868 when the Wellington Volunteers played the crew of the HMS Falcon. A low-scoring affair, the Falcon crew chased down the 38 runs they need to win with one wicket to spare. After the match, the umpire apologised to the players for the stony, thistle-covered ground. From there, cricketers invested heavily in the ground so, by the 1880s, the Basin Reserve was almost unrecognisable from a decade before; picket fences, the Caledonian Stand, and a vastly improved playing surface meant cricket was here to stay.

The original layout of the Basin Reserve was rectangular, large enough to fit two soccer fields. This meant that it was not uncommon for several club cricket matches to be played at the ground at once. It was a different story for big matches, when every inch of space was needed to fit the large crowds that would flock in. When Lillywhite’s All England XI visited in 1877, cricket was so popular in New Zealand that a holiday was proclaimed and schools closed for two days. Six weeks after playing at the Basin Reserve, the same All England side would feature in cricket’s first Test match, playing Australia at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

New Zealand’s first Tests were played against England in 1930. After the visitors won the opening Test in Christchurch, the Basin Reserve hosted the second Test starting on January 30. Here, on his home ground, Wellington opening batsman Stewie Dempster made history with New Zealand’s first Test century. Moments later Jackie Mills, on debut, added his own as the pair put on an opening partnership of 276 – still New Zealand’s highest, for any wicket, against England. In 1969 another historic first century was scored here as Trish McKelvey hit 155* against England, New Zealand’s first women’s Test hundred.

Today, the Basin Reserve has seen more New Zealand Test matches, and Test victories, than any other ground. It has also been the venue for some of the most remarkable performances in our cricketing history; from JR Reid’s 15 sixes in a first-class innings, to Martin Crowe and Andrew Jones’ World Record partnership of 467 in 1991, and Brendon McCullum’s historic score of 302 in 2014.